If you are working with human beings at all you will find yourself negotiating. Two definitions of the word negotiate that I like are “to obtain or bring about by discussion” and “to find a way over or through a difficult path or obstacle.” Put those together and negotiation comes to mean the navigation of a process to overcome obstacles primarily through the means of discussion.

And that navigation is not easy.

Even when individuals are from the same culture, negotiations can be complex and difficult despite having a set of similar cultural behaviour expectations to guide the conversation. For example, people from similar cultures tend to keep the expected distance between each other when speaking, use like gestures, and observe cultural hierarchy and gender norms without even knowing they are doing these things. They know what the “accepted” beliefs, values and behaviours in the workplace are likely to be and how far they can deviate from the accepted behaviours without penalty. All this unconscious knowledge about how to behave when with your own in-group makes the negotiation process understandable to both parties.

But what if all the assumptions you usually make about how other people will behave turn out to be wrong? What if the other party bows when you try to shake hands, looks away when you look up, stares when you would not even glance, laughs when you don’t expect it and shows either too much or not enough emotion from what you would expect? How do you negotiate under those circumstances? How do you know what is personal, what is cultural, and what is in between?

Some people have described the experience of negotiating between cultures as trying to dance on a constantly shifting dance floor. I would add to that image that you are dancing with a partner you don’t know, music neither of you recognize and each of you is using dance steps from different dances. Not too comfortable is it?

This 3-part series of articles will discuss different cross cultural negotiation strategies. In this post we will work with 7 power strategies and throughout the series will refer to the following workplace example borrowed from interculturalist Andy Molinsky to contextualize what cross cultural negotiation looks like.

A Chinese and American cross-cultural negotiation opportunity

A Chinese professional, Cheng, was told by his boss to show leadership potential in meetings by not only expressing his personal opinion, but also by occasionally directly disagreeing with his superiors. It’s important to understand that neither Cheng nor his boss are aware of their own hidden cultural assumptions which is somewhat obvious…I can only imagine Cheng’s horror at being asked to do this. As a Canadian I would be uncomfortable, but as a Chinese, it must have felt like committing a crime!

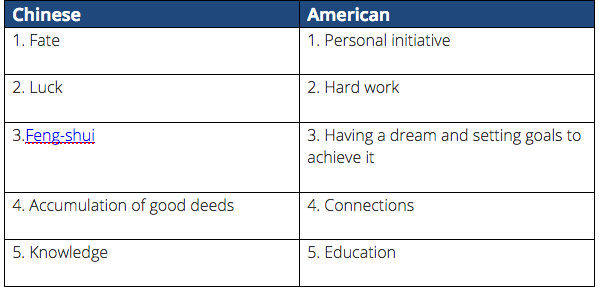

Cheng’s confusion can be understood in part by looking at Table 1 below: it summarizes research adapted from Pitta, Fung and Isberg (1999) to supply a cultural values comparison to better understand the barriers Chinese and American negotiators have to overcome to reach an agreement.

Table 1: Chinese and American cultural workplace values

Can you see why there might be some difficulties in communication between the two cultures?

A quick look at the table below shows why Cheng might find this request from his boss to clash with his values and why his boss may be completely unaware that what he has asked Cheng to do could be misunderstood.

While some similarities between knowledge and education evidence similar workplace values, the other values listed on the table seem more dissimilar. Consider the differences in the way personal agency is perceived or how the control of destiny is believed to impact a person’s life: they are almost completely opposite.

The underlying Chinese Confucian understanding is that since destiny is predetermined, people should not attempt to interfere with it. Add the influence of communism where many personal decisions are outside of an individual’s control and where dissent could bring punishment and even death, and it is apparent why in most circumstances publicly disagreeing with superiors is a deeply problematic idea for the Chinese.

Conversely US cultural values have developed from many diverse populations migrating to a new place to forge a new life in an unknown and often harsh environment. In this context, learning to stand

ground and claim a place among other populations encouraged a national attitude of pride in uniqueness and ability to rise above the crowd and shape circumstance to your benefit.

Of course with the rise of materialism, the internet, and more opportunities for intercultural contact, many Chinese are showing higher individualism and initiative while many Americans pursue greater mindfulness and collective identity. There may be some possibilities for negotiation from this mutual cultural curiosity as each side gets a bit closer to the other side’s lived experience.

Returning to the story of Cheng and his boss, Cheng swallowed his initial horror at the request to disagree with his boss publicly because he wanted to do well and please his superior. He later chose what seemed like a golden opportunity to tell his boss how “crazy” his boss’s idea was and to explain how many things his boss had missed in his analysis of a particular problem. Cheng was quite proud of his capacity to try out this new “disagree with the boss” behaviour and waited expectantly for approval from his boss. As you can imagine, things did not go well for Cheng and his boss was not in the least bit happy.

The effect on Cheng was confusion and a heavy heart. He did not understand the American cultural norms well enough to be able to perform them subtly and now realized he had made a significant workplace mistake without having any idea how to smooth things over. In the same way, Cheng’s boss had no idea how to coach his Chinese employee because his understanding of Chinese cultural norms was limited.

To help this workplace incident find some negotiation strategies, let’s consider a few ways people have carried out cross cultural negotiations over the past two or three thousand years and how they continue today.

Power-based negotiation strategies

Most negotiations depend heavily on power difference between two parties. Historically power-based negotiations between cultures imitate one or two of the following seven approaches. To begin we will outline the separate strategies and discuss the benefits and drawbacks of each:

#1. Avoidance

If the cost of confrontation is high, the stronger party could avoid dealing with the issue and continue to maintain the status quo. For example, people can choose to ignore incidents of human rights abuses to ensure ongoing flow of products and services from one company/country to the other.

- Benefits: Maintains power and stasis temporarily

- Drawbacks: Will likely result in outburst or unpleasant outcome when weaker party has had enough. Alternatively the weaker party will become so weak from the inequity that it will no longer be able to hold up its side of the deal.

#2. Forcing

In forcing, the stronger party simply demands its way as when powerful multinationals force smaller contractors to adopt their accounting systems if they want to get paid.

- Benefits: Stronger party gets what it wants

- Drawbacks: Weaker party is resentful and will look for a way to find a better partner when available; exhibits weak loyalty. Stronger party has the illusion of invincibility and comes crashing down when there is a coup

Ready to resolve intercultural conflict better?

Check out our FREE online course “Work and Culture” and get introduced to cultural concepts for success in the Canadian workplace.

#3. Education and persuasion

In this strategy, the stronger party explains the benefits of ideas using human psychology, by exploring the parameters of social behaviours or through applying spiritual principles. Consider the following examples:

- A union shows the increased bottom line as related to worker safety practices in a contract negotiation meeting

- The persuasion of another party over time to try a different approach using psychology, sociology or principle, and an evidenced effort to provide support in an effort to promote a feeling of reciprocity

- The inclusion of worker safety as negotiation point on agenda prior to signing final agreement where the contract outlines onsite support for three months to help teach the new safety behaviours and implement policies

- Benefits: Workers are safe, both sides learn from each other, better business decisions are made

- Drawbacks: Takes time, effective education is not easy across cultural differences, not everyone applies the new principles the same way, not everyone understands the relationship between the initiative, the attitudes, the behaviours and what is expected of them personally to make it work. When strong leadership for the initiative is replaced, sustainability becomes difficult

# 4. Infiltration

Here an idea is introduced over time using multiple channels until it takes root in the popular imagination, for example ISO standards are now seen as necessary for raising international standards on product and service quality.

- Benefits: Power of the masses supports the idea once it has been adopted by the majority of the population (Example: No smoking in public places is now considered the norm in most places in North America)

- Drawbacks: It can take years for this method to take effect and it can also be difficult to control if misunderstandings become mixed into the original message. Since positive triggers are complex, people do not always act in predictable ways for beneficial changes, although mob mentality and negative change triggers can be predicted.

#5. Negotiation and compromise

#6. Accommodation

Here one party simply agrees to do what the other party wants, adopting their protocols and values, as what occurs in many mergers and acquisitions.

- Benefits: May be the only way a business agreement can be reached, so a contract can be negotiated and jobs ensured

- Drawbacks: Could backfire since it is difficult to “adopt” another system. Usually fails at a shockingly high rate of over 90%[1]

#7. Collaboration and problem solving

In this strategy, both (or several) parties work together until a mutual agreement is reached. Consider when multi-stakeholder oil and gas providers, mining or forestry project managers, Aboriginal and Environmental groups join to negotiate business deals that involve communities, land and resources.

- Benefits: Has highest probability of solving a problem and is likely the most sustainable

- Drawbacks: Extremely time consuming and laborious, difficult to keep both parties motivated throughout the process. Dependent upon good will of both/all parties and very mature negotiators who can deal with difficult conflicts and unreasonable expectations without losing their minds in the process

To summarize these strategies, people have been negotiating across cultural differences for a very long time and they have developed more or less successful systems within which almost every culture can see a local example, with specifics according to context and history. This framework does provide some common ground for negotiation processes although many of the strategies listed above are neither satisfactory nor equitable.

Making Predictions

Back to Cheng and his boss. Could any of the above strategies work for them to re-negotiate their difficulties? The most promising is collaboration and problem solving, where both learn from each other and both enjoy a better working relationship. Unfortunately, that is unlikely given that both are not aware of the influence of culture in their particular context, and the fact that the boss made this request in the first place shows he is more likely to demand than to collaborate. Finally, the boss in his power position has little incentive, either positive or negative, to adapt to Cheng.

What is likely to happen is accommodation. Cheng will continue to give in to what his boss is asking and get closer and closer to an understanding of what the expected behaviour from his boss is. If he is paying attention, Cheng will realize that there are sophisticated rules surrounding how and when you disagree with your boss in the US, the tone you should use, and the approach that shows you are on your boss’s side, while expressing disagreement. The stakes are high for Cheng; if he is not observing closely and taking mental notes, Cheng will likely lose his position, or be passed over for promotion.

Power-based negotiation strategies have both benefits and drawbacks and they are only one way of conceptualizing what intercultural negotiation can look like. The next two posts will consider how Cheng can use influence and personality based strategies to negotiate more effectively with his boss.

[1] See: http://www.businessrevieweurope.eu/finance/390/Why-do-up-to-90-of-Mergers-and-Acquisitions-Fail

Looking for more ways to build your career? Check out some FREE online learning that can help you learn to resolve cultural misunderstandings in your workplace.

“Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life”

Marcus Aurelius